“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness”.

Charles Dickens’ famous opening of the novel A Tale of Two Cities is as accurate a description of today’s global issues as it was for Europe around the French Revolution. But is this the best or the worst of times for civil society organisations?

Today, many societies are shaken by the failure of established institutions to address global problems like wars, environmental catastrophes or just the worries of ordinary citizens over their future. As a result, people lose trust in governments and media, multilateralism is in the firing line, and the future of democracy is unclear. And admittedly, the world does not look good for those propagating tolerance, humanistic values, global solidarity and human rights.

But every trend has a countertrend.

While populism and authoritarianism seem to increase in influence, they are countered by new and vocal forms of civil activism. Youth movements, like the increasing number of school strikes, fight inertia around climate change on the streets. The rise of illiberal Civil Society has prompted a re-emergence of moral and ethical debates around a “common humanity”. Attacks on human rights and values are being pushed back through acts of solidarity and new empathic narratives. And chauvinistic attitudes and patriarchal patterns give way for liberal and feminist agendas, from the #MeToo movement to explicit feminist governments like Canada or Sweden, aiming at greater equality of opportunities for all.

A key development is that societal trends, good and bad, are exacerbated by the rapidly evolving information technology. Division of society is being amplified by fake news and online manipulation in social media, yet the Internet connects half of the world’s population and provides the greatest imaginable opportunity for global learning, exchange and transparency. And plenty of “technology for good” debates show growing concern and responsibilities in dealing with the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

The renowned think tank Carnegie Endowment sums it up well: “The world is at a transformational moment, defined by cataclysmic threats and unimaginable opportunities”.

Civil Societies role in shaping the new global world order

Many expect civil society to be the leading force in shaping these opportunities around a new global world order. While traditional civil society organisations have lost some of their soft power, they still form a sector of high credibility, outreach and positive impact on the lives of the people. But there are three important steps that CSOs will have to take to live up to the challenge.

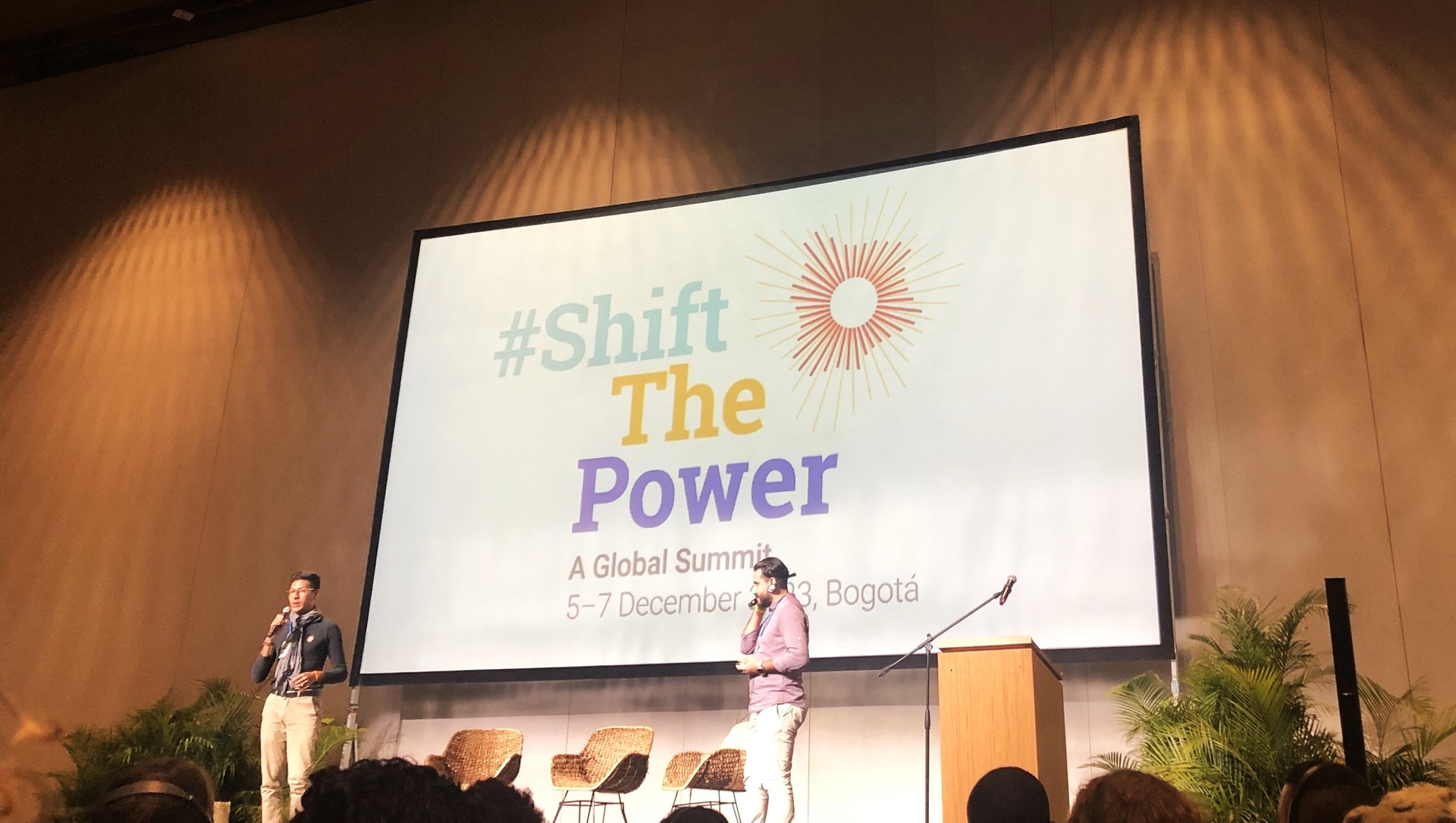

Firstly, they need to reflect on their own way of working, the way they engage with citizens, and how far they are still visibly and convincingly connected with their missions. Legitimacy of international civil society organisations needs to be earned on a continuous basis, particularly when it comes to representing and reconciling minority and majority positions of the people they serve, and of those that support their work. Established power structures within organisations and within the sector need to be challenged. Likewise, those organisation lacking engagement with local movements and imbalanced partnerships with community-based organisations needs to be called out. Civil society must make sure to always keep an arm’s length distance from governments and for-profits, and make sure they don’t become instrumentalised for political agendas. At best, civil society shapes dialogues and collaboration with others outside the sector and drives global solidarity debates and actions, advocating for change when engaging with elites.

Secondly, civil society organisations need to embrace truly innovative approaches towards significant threats that are undermining the wellbeing of future generations. Innovation comes with the need to say goodbye to outdated business models reflecting a false “North-South” power structure, drop anachronistic messaging and . By focusing more on necessary societal adjustments in industrial countries CSOs can address, for example, the failures of the Global North to fight climate change. It requires courage to try and fail, persistence to scale up promising and successful initiatives, and to continue learning within and outside the organisation. It also means stepping aside when others have better ideas, and when a new generation is ready to take on the challenge. It also means powering new societal conversations about critical issues which will affect everyone in future – like what jobs and income will look like in a post-manufacturing, Artificial Intelligence-enabled world. And while digitalisation is a big part for possible innovation in the sector, it is by far not the only means, and one should not overlook analogue, local, citizen-generated and decentralised strategies to tackle threatening problems.

Thirdly, collaboration needs a step change between CSOs and possible allies within and outside the sector. Civil society is the sphere of dialogue, innovation and reinvention. Intersectional partnerships should free resources and multiply impact. Lessons are desperately needed and can derive from looking beyond organisational boundaries, and scanning the horizon for opportunities to join up should be a constant part of CSOs’ work. Territorial thinking or the focus on brands and logos need to be a thing of the past; instead, robust and more effective mechanisms for joint actions of solidarity within and beyond the sector should be developed to counter the organised attacks on civic space worldwide.

The International Civil Society Centre works with social justice, environmental, and human rights organisations who have an immense outreach, delivery power, resources and political influence. It provides room for accelerating the reflection, innovation and collaboration we need, and invites every sector to join its ambitions. In the coming months, we will focus on addressing authoritarian and populist attacks on the values that form the basis for Civil Society’s work, and will provide opportunities to collaborate across sectors towards the aim of a new “common humanity”.

In taking these actions we would be closer to Charles Dickens vision at the end of his book: “I see a beautiful city and a brilliant people rising from this abyss, and, in their struggles to be truly free, in their triumphs and defeats, through long years to come, I see the evil of this time and of the previous time of which this is the natural birth, gradually making expiation for itself and wearing out”.