We looked at three factors in order to decide which initiatives to highlight: innovativeness, effectiveness in countering populism, and responsiveness to the potential of digital media in the specific context, either as an enabler of populism and/or the innovative response.

How we define innovation

In this report, we have defined innovation as “an iterative learning process which identifies, adapts/adjusts and shares novel ideas for improving civil society action, impact and operating space”.

When we assess whether an initiative is innovative or not, we examine whether it is different from prior or similar initiatives in the following ways:

a) What does it tell us, and what can we learn, about previously unseen opportunities or risks in the relationships among civil society, populism and media?

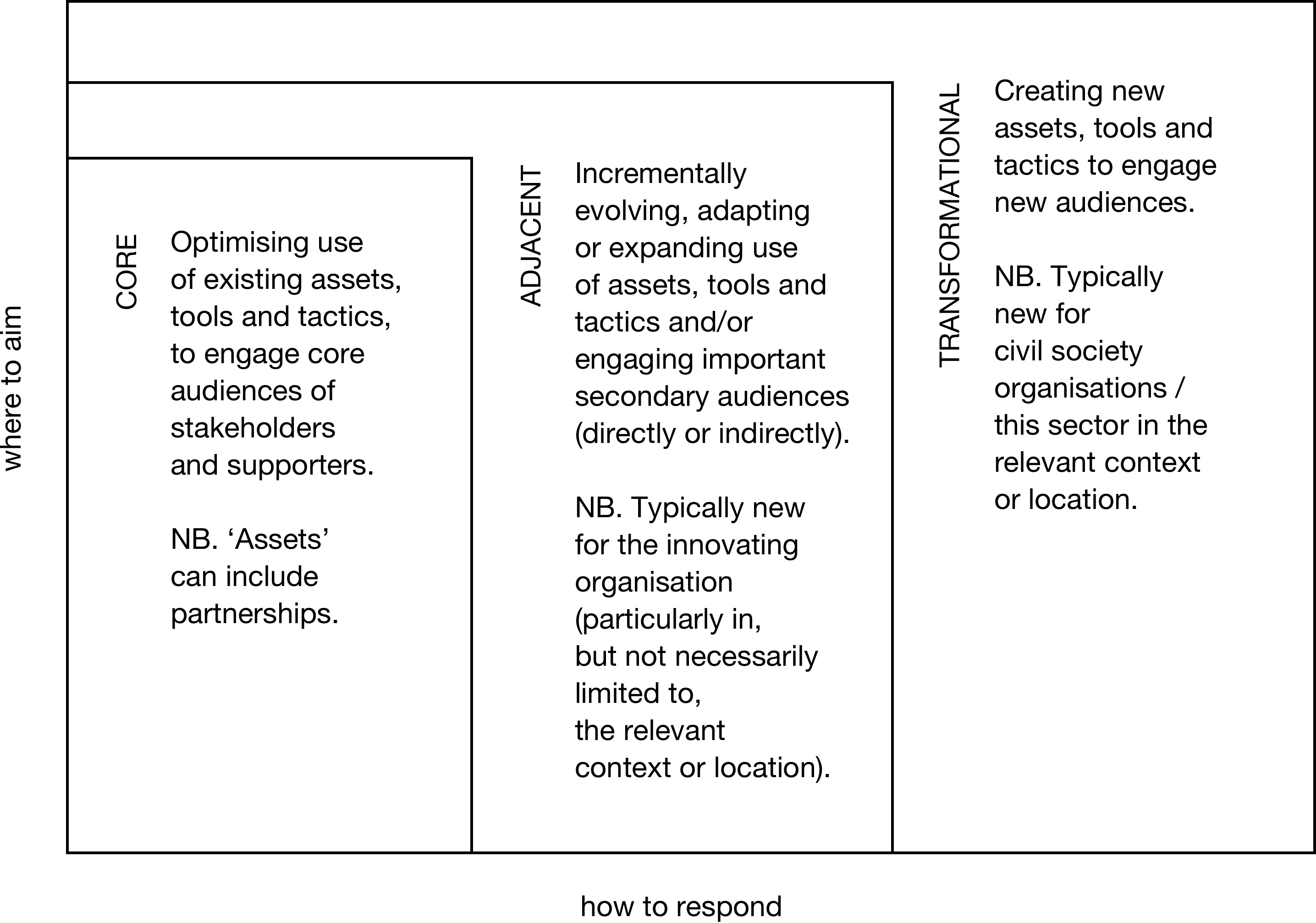

b) Does it adopt new tools or strategies and/or appeal to new audiences? We look at two main dimensions: “where to aim” (audiences) and “how to respond” (which include assets, tools and tactics; assets can include partnerships).

For our civil society audience, we have redefined the specific categorisations adopted for our innovation model using the “Innovation Ambition Matrix” (see chart below, adapted from www.doblin.com), further refining a classic diagram from the mathematician H. Igor Ansoff to help the private sector allocate funds among growth initiatives. These are as follows:

Innovation maturity definitions

For each case study, we have also indicated the stage of the innovation, as follows:

|

experimental |

The innovation is at or near the start of implementation, or in a pre- implementation or preparation stage (i.e. beyond a concept and with organisational commitment and practical planning in place). |

|

No evidence or lessons are yet available to inform either its iteration/adaptation or assessment of its effectiveness, influence or impact. |

|

|

emerging |

The innovation is in the process of being implemented. |

|

Some evidence or lessons may be generated to inform iteration/ adaptation of the innovation and to assess if it is demonstrating effectiveness, influence or impact. |

|

|

established |

The innovation has been fully implemented. |

|

Evidence is available to assess if and how it has been effective or achieved influence or impact. Wider lessons or conclusions can be shared with others. |

how we define populism

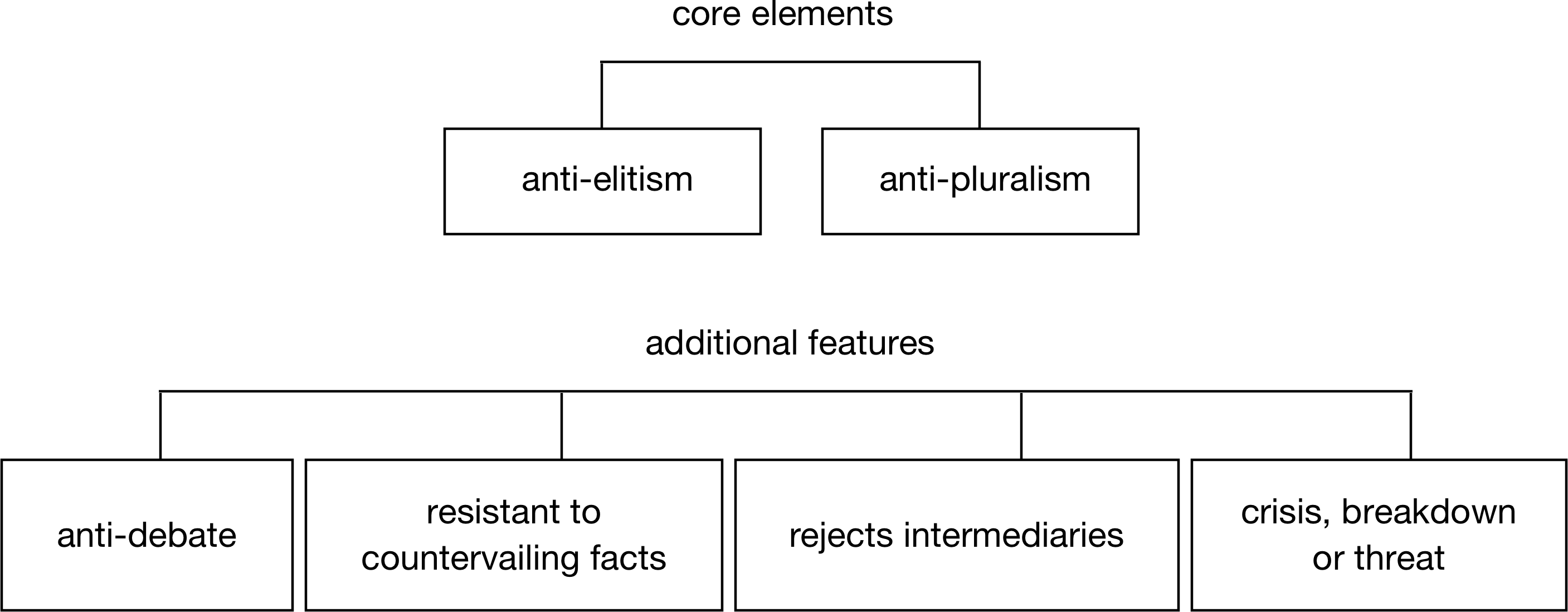

We limited our search for innovations to those that respond to different facets of populism. We define populism as having two core elements:

a) anti-elitism

b) anti-pluralism

with four additional features:

i) anti-debate

ii) resistant to countervailing facts

iii) rejects intermediaries

iv) deploying crisis, breakdown or threat

As a “thin-centreed ideology”, meaning it does not, in itself, pre- scribe specific policies or political ideologies, populism can be found across the political spectrum: left, centre and right. Yet it is often tied to “thicker ideologies” that prescribe sets of claims about the world, such as socialism, fascism, nativism and authoritarianism. These “thick ideologies” are accompaniments, but not intrinsic elements, of populism.

two “core elements”: anti-elitism and anti-pluralism

Anti-elitism presupposes the existence of a “real people” that the populist alone claims to represent. In these narratives, the “real people” struggle against a corrupt and immoral “elite” that not only oppresses the “real people” but also protects or coddles supposedly illegitimate groups considered as the “other”, such as migrants and minorities who commit crimes and rob the “real people” of opportunities. This explains why marginalisation and/ or scapegoating of already marginalised groups, communities or constituencies is common in populist contexts. Moreover, the definition of the “elite” is frequently defined by the populist. In the United States, the billionaire President may be considered “elite” by standard definitions. Yet he has successfully managed to redefine the “elite” as the traditional Washington establishment, thereby casting himself as an outsider working on “the people’s” behalf. Further drawing on these polarising concepts of “us” and “them”, some have classified three types of populism.

|

cultural populism |

socio-economic populism |

anti-establishment populism |

|

|

the people |

Native members of the nation-state |

Hard-working, honest members of the working class, which may transcend national boundaries |

Hard-working, honest victims of a state run by special interests |

|

the others |

Non-natives, criminals, ethnic and religious minorities, cosmopolitan elites |

Big business, capital owners, foreign or ‘imperial’ forces that prop up an international capitalist system |

Political elites who represent the prior regime |

|

key themes |

Emphasis on religious traditionalism, law and order, national sovereignty, migrants as enemies |

Anti-capitalism, working-class solidarity, foreign business interests as enemies, often joined with anti- Americanism |

Purging the state from corruption, strong leadership to promote reforms |

Three ways that populists frame “us vs. them” conflict

Anti-pluralism supposes that the will of “the people” can only be defined by the populists themselves, thereby transposing their decisions into larger moral claims that are not subject to contrary evidence. Moreover, by conceptualising complex societies into homogeneous “us” and “them” categories, populists fail to integrate diverse perspectives, voices and interpretations into situations and conflicts. To galvanise support, they tend to leverage emotions, values and the sense of belonging. In so doing, they often couch their policy decisions and issues in a simple and straightforward manner, oversimplifying situational analyses and solutions. Populists do not want to countenance the need to recognise and accept a more complex or perhaps contested reality, with different ideas, opinions and perspectives to consider on these issues.

Four additional features of populism

Populism is anti-debate. Civil society and human rights organisations naturally promote debate as a way of testing government policy and distilling the best ideas for social change. But since the legitimacy of the claim of the populist leader to represent “the people” is couched in symbolic and moral terms, as opposed to facts or verifiable will gleaned through processes of contestation such as elections or legislative debate, it is therefore immune from questioning. Indeed, while debates and elections occur in populist contexts — in fact, populists tend to utilise elections a lot — they are rarely genuine contestations of discourse or power. Instead, these elections and debates masquerade as civic discourse in order to bolster the perceived democratic legitimacy of the leader, leading the political scientist Jan-Werner Muller to claim that “populism without participation” is hardly ironic.

Second, populism is resistant to countervailing facts. Exposés of corruption or even crime do not necessarily bring down populists because they can justify their behavior as attempts to redistribute wealth and opportunities to “the people” that have traditionally been limited to elites. This explains why populists, unlike secretive dictatorships, can be brazenly candid about engaging in corruption. In contrast, civil society and human rights organisations thrive on facts. They document violations, provide evi- dence for decisions and present findings in a professional, if sometimes technocratic, manner. According to Benjamin Moffitt’s The Global Rise of Populism: Performance, Political Style, and Representation (2016), technocracy is populism’s opposite:

Each of the features of the technocratic style are [sic] directly opposed to the features of populist political style. While populists appeal to “the people” versus “the elite” and argue that we should trust “common sense” or the wisdom of “the people”, technocrats place their faith in expertise and specialist training, and by and large do not concern themselves with “the people”. While populists utilise “bad manners” in terms of their language and aesthetic self-presentation, technocrats have “good manners”, acting in a “proper” manner in the political realm, utilising “dry” scientific language, dressing formally and presenting themselves in an “official” fashion. This divide is also marked by the role of affect and emotion: while populists rely on emotional and passionate performances, technocrats aim for emotional neutrality and “rationality”. Finally, while populists aim to invoke and perform crisis, breakdown or threat, technocrats aim for and perform stability or measured progress. Here, the “proper” functioning of society is presented as being able to be delivered by those with the requisite knowledge, training and standing.

Third, populism rejects intermediaries. While democratic leaders traditionally communicate with the public through formal channels such as representatives, political parties, or from behind a podium, populist leaders emphasise direct communication with “their people” and undermine entities that seek to mediate and qualify these relationships. In Venezuela and Ecuador, Rafael Correa and Hugo Chavez, and now Nicolas Maduro, have held regular and lengthy unscripted weekend talk shows that convey the illusion of speaking directly and candidly with the public. As only the leader represents “the people”, political parties, independent courts, the media and civil society are excluded from intervening in the relationship between the populist and the public.

Finally, populists thrive on crisis, breakdown or threat. In so doing, they justify extraordinary measures — the building of walls, the arrest of opponents without due process, or the waging of a “war on drugs” — in order to protect “the people” against perceived existential or conspiratorial threats. Such threats also justify the populists’ identities as outsiders and reformers of the existing structural order, allowing them to pose as the “solution to the crisis”.

How we consider digital media

For the innovation case studies, we look at the role of digital media either in the context of the problem or as part of the innovative solution. In terms of the problem, is digital media a trigger, an enabler, a mediating factor or a barrier to populism? As for the solution, does the initiative transform the role of digital media, take advantage of its potentialities or blunt its negative potential in the specific populist context?