This is the first of two guest blogs and an upcoming podcast interview which will explore longstanding challenges and new dimensions of deep drivers of change for international civil society organisations (ICSOs), from a group of academics and practitioners who have long explored the questions of power and relevance that influence the future of these organisations.

In this first blog, the authors explore the major long-term trends and questions already challenging the sector before the new complexities highlighted and surfaced by the big developments of 2020.

—

Long before COVID-19 disrupted the lives of billions and raised new, urgent challenges for the sector, many ICSOs were already grappling with existential questions about their futures. In many ways, the global pandemic is amplifying a longstanding need for change, not just for future-looking ICSOs but for the whole sector more broadly.

Geopolitical shifts, increasing demands for accountability, and growing competition have been driving the need for change within the sector for decades. ICSOs have been responding with specific initiatives intended to secure their future effectiveness and relevance, but their efforts have been constrained by institutional and cultural legacies—forms and norms—that inhibit their ability to successfully adapt. As ICSOs confront unprecedented challenges to their survival and future relevance, leaders and change managers must keep the long-term future in sight while addressing the immediate needs of their organisations and stakeholders.

New agency within old architecture

The longstanding problem facing ICSOs is that over the past half-century they have evolved into new kinds of organisations, while the architecture in which they operate has remained largely unchanged. Most ICSOs today do more than alleviate the symptoms of deprivation and injustice, seeking instead to address root causes through fundamental social and political transformations. As such, they are no longer conventional charities and instead agents of transformation focused on achieving long-term sustainable impact.

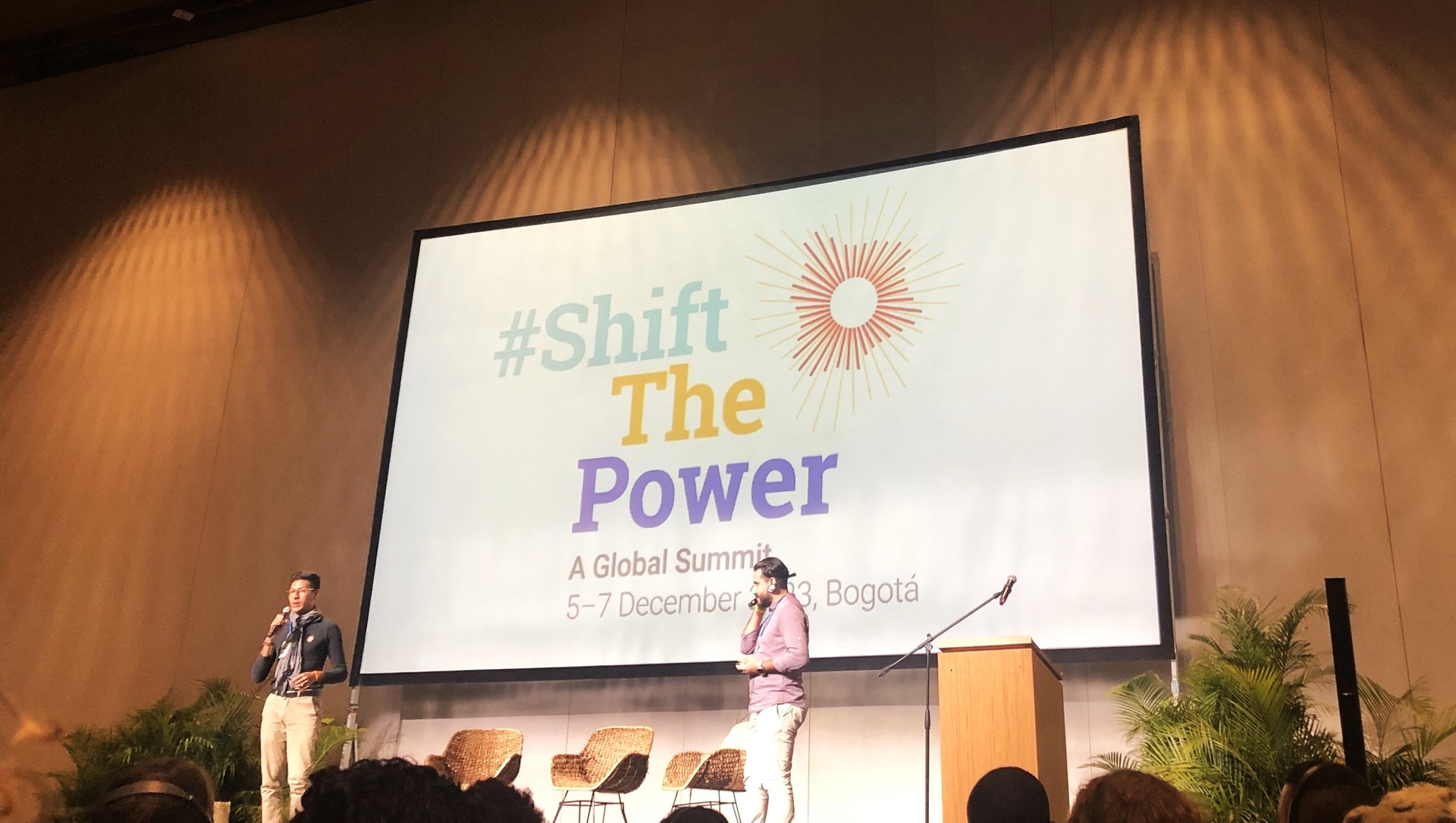

But ICSOs still operate within a legacy architecture designed for conventional charities, not for contemporary change agents. The resulting tensions underlie many of the challenges long debated throughout the sector, including aid localisation, downward accountability, and shifting power. Missing in these discussions is an acknowledgement that ICSOs need to do more than embrace internal reforms; they also need to work collectively to change the architecture in which they are embedded.

The legacy of the architecture and its accountability framework

The architecture consists of the forms and norms that have historically defined the sector. In the United States, ICSOs typically incorporate in charity form with self-perpetuating boards and transnational federated governance structures often dominated by their wealthiest member organisations. These forms tend to privilege ‘upward’ financial accountability to donors in the Global North, with a focus on preventing financial integrity failures, such as embezzlement or fraud, rather than focusing on ‘downward’ accountability and sustainable impact for intended local constituents.

The charity model assumes that the impact ICSOs create is often unknowable or too difficult to measure, so accountability is instead fixated on financial reporting and monitoring. In general, ICSOs are supposed to spend all of their available resources as quickly as possible on whatever is easiest to measure and most satisfying to donors. This is not conducive for organisations explicitly committed to being accountable to those they claim to serve, truly empowering stakeholders, and achieving long-term sustainable impact. The traditional charity model works well for conventional charities, but fails for ICSOs seeking to inhabit new roles as agents and facilitators of fundamental change.

Manifestations of dysfunctional architecture and cultural norms

The dysfunctional role of this architecture is today particularly apparent when ICSOs attempt to break the rules to increase their effectiveness; for instance, when activists seek to address global issues through advocacy “at home,” rather than through traditional aid transfers from the Global North to the South. In Germany, groups such as Attac and Campact had their tax-exempt status revoked because of tax laws prohibiting political activities. In Switzerland, a recent campaign by ICSOs in support of greater corporate accountability for human rights violations abroad has led to accusations of engaging in illegal domestic political activities. As the strategies of ICSOs continuously evolve based on changing understandings of global problems, the existing charity laws and regulations regularly fail the sector.

Alongside issues of law and governance, powerful cultural sector norms have also emerged that influence how stakeholders think and act. Many of these represent the sector’s virtuous character and should be maintained and celebrated, but others hold it back. For example, ICSO staff and supporters may acknowledge a need for reform throughout the sector, but at the same time consider their own organisations exempt because of some perceived unique difference. These ‘excessive cultures of uniqueness’ can also lead to problematic behaviours by individuals claiming a commitment to values as a substitute for a true culture of transparency and openness.

Transforming the architecture together

Of course, what ultimately matters most is the lives of the billions of people who stand to gain by a more successful sector. The architecture has ensured that ICSOs can survive, and even thrive, mainly by satisfying resource providers. But this system is outdated and fails to serve the needs of ICSOs and their local constituents today.

To ensure their future relevance, ICSOs need to collectively organise to transform the legal and cultural frameworks holding the sector back. They need to decide what kind of organisations they want to be and then help create a new architecture that facilitates, rather than impedes, success in these desired future roles.

—

George E. Mitchell and Hans Peter Schmitz, alongside Tosca Bruno-van Vijfeijken, are co-authors of the recently published book Between Power and Irrelevance: the Future of Transnational NGOs. You can discover more details about it here.