Kenya is steadily moving towards the full realisation of child rights but there continues to be substantial disparities across the country. While there has been progress in school enrolment, child survival and a reduction in female genital mutilation there are still challenges in gender equality, public participation and access to essential services. The 2010 constitution and related policies make provisions for entitlement to services and participation however, there have been weaknesses in the implementation of these legal and policy frameworks.

During the lead up to the Kenyan national elections in 2017 children across Kenya took part in a children’s charter calling for their voices to be heard in the governance agenda. Over 40,000 children from all social backgrounds expressed their concerns on the Government’s development plans following coordinated and sustained mobilisation over a seven-month period. The result has been an increase in agency with more children embracing their role in making change happen; an activated youth network campaigning on a range of similar issues and commitments from local government leaders.

What is the Children’s Charter?

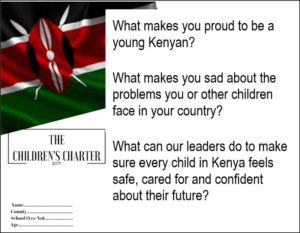

The children’s charter represents the socio-political concerns and aspirations of young Kenyan children across the country. It started with a postcard campaign across schools, communities and county assemblies, where face-to-face meetings were held with children to discuss the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) framework and its importance to local and national development plans. Children were then asked to reflect on their own circumstances, the issues that concerned them and what action they would like to see from Kenyan leaders.

The postcard data was collected, analysed and further discussed with children. Many believed that the Government’s provision of free primary education was a significant achievement, they also felt proud to be citizens and wanted a peaceful environment to grow up in. The concerns emerging from children were violence and the continued barriers to education, peace and food security.

Based on these results representative groups of children[1] drafted local charters with recommendations for county development plans. With the support of partners, children were able to hand over and discuss the recommendations with local politicians, this was a significant achievement at the time given the political attention on the re-election process unfolding in the country.

The local charters were then consolidated into a national Kenyan Children’s Charter which was launched on Universal Children’s Day in 2017 by child representatives from each county.

How has the charter influenced the political agenda?

At the time the charter was presented, decision makers showed interest in the recommendations with some making explicit commitments to address concerns raised. There is evidence that some draft development plans are capturing issues raised and in Bungoma County a rescue centre has been constructed as a result of the consultation.

Furthermore, some of the children have now become involved in child-consultations on amendments to the Children’s Act calling for provisions to involve children in public participation processes.

The Kenyan Constitution and legal framework place a strong emphasis on public participation in decision-making. When presenting the children’s charter, children explained that if they represent more than 50% of the Kenyan population and are not being consulted, then the law is not being properly implemented. They asked for the creation of spaces for child participation so they can systematically be part of the decision-making process.

How did the charter represent diverse voices?

During the seven-month mobilisation period there was a deliberate effort to ensure the most excluded children in all countries were represented in this process. Approaches included working with sports associations, utilising popular moments (such as the Day of the African Child), and an emphasis on the leadership of children’s networks and local agencies. With greater representation across counties strong partnerships allowed us to reach a higher and more diverse number of children[2]. Partners included Child Fund, Mtoto News, World Vision, Mathare Youth Sports Association, Moving the Goal Post football and Save the Children.

What have we learnt?

The initiative is one of largest public actions in the global south within Save the Children, with significant learning for future ambitions to ensure children are supported to have a voice within civil society. The opinions gathered by children have helped Save the Children to further clarify its focus in Kenya within its next strategic plan.

For many participating children the charter hand over represents the first opportunity for them to engage with decision makers. We have observed an increase in self-confidence among young people along with more interest from decision makers and the media.

Partnership, transparency and pooled resources have been important principles underlying the project, creating joint ownership and trust.

Lastly, the simplicity of the postcard tool for surveying the views of children encouraged high numbers of participants. It allowed children from eight to eighteen to express their concerns and recommendations in a simple way that was easy to disseminate across the country.

What next?

As time passes we will start to see the full impact of this approach, but for this to happen children and partners will need to be involved in monitoring and accountability of political promises. The partners in the project will be supporting children to monitor commitments and implementation and continue to utilise the charter and popular platforms.

[1] Children are elected in each county to represent their peers and they meet quarterly to discuss concerns and issues raised by their constituencies.

[2] Children’s networks lead on the framing of priorities and presentation to decision makers; child focused agencies facilitated the participation of children; media agencies ensured there was visibility and wider public engagement; a wider network of supporting agencies (schools, youth clubs, business etc) supported the logistics and coordination of the process.