A few weeks ago I recruited a new colleague to our small Centre secretariat team. The pattern of many previous rounds was repeated: We reviewed a number of very qualified and competent young female candidates, struggled to invite equally impressive male applicants for an interview and in the end offered the position to a very dedicated, ambitious and talented woman who wants to develop a long-term career in the civil society sector. I have met and worked with many women like her over the years at the Centre and in the civil society organisations (CSOs) we work with.

But very few of them advance to the senior management positions they aspired to take on when they start their career in the CSO sector. Looking at the leadership of the majority of large CSOs, these women never make it there. According to data from 2012, the Women Count report, women make up 68% of the workforce of the 100 CSOs with the highest income in the UK but only 25% of the most senior positions. In Germany, about 75% of the workforce are female; in CSOs providing social and care services the number even goes up to 83%. However, only about 42% of CEOs are women, sometimes only in co-leadership with a man. Of the roughly 30 leading international CSOs we work with at the Centre, only one third have a female global CEO. The representation in boards is by no means more gender balanced.

So what happens on the way to formal leadership positions? The very few studies that focus on the CSO sector suggest the “typical” explanations: Women can’t or don’t want to work full-time because of family responsibilities and therefore remain in the operational low to mid-level positions; male Board and CEOs recruit and promote “look-a-likes” to work with them or succeed them and women themselves hesitate to take on formal leadership roles because of their own prejudices and doubts whether they are ready or well-equipped enough.

Our sector is leading the way on gender balance and gender justice in programming, advocacy and research. Most large CSOs have mainstreamed gender issues across all their work with very impressive results for women’s empowerment worldwide. But when it comes to our own organisations we lag behind many other sectors who have systematically started to increase female leadership, sometimes only under pressure from governments who introduce quota, but also because they understand that gender balanced management achieves better results (and profit) and that it simply does not make sense to leave a large part of their talent pool untapped.

The gender imbalance in our own organisations’ leadership should no longer be acceptable for us. How do we systematically support women in their career development so that they acquire the skills and qualifications but also the confidence to apply for and accept formal leadership roles? What can our organisations do to provide the work conditions and culture in which women thrive just as much as men? How can we change our recruitment, retention and promotion processes in a way to increase gender balance within our top leadership and governance?

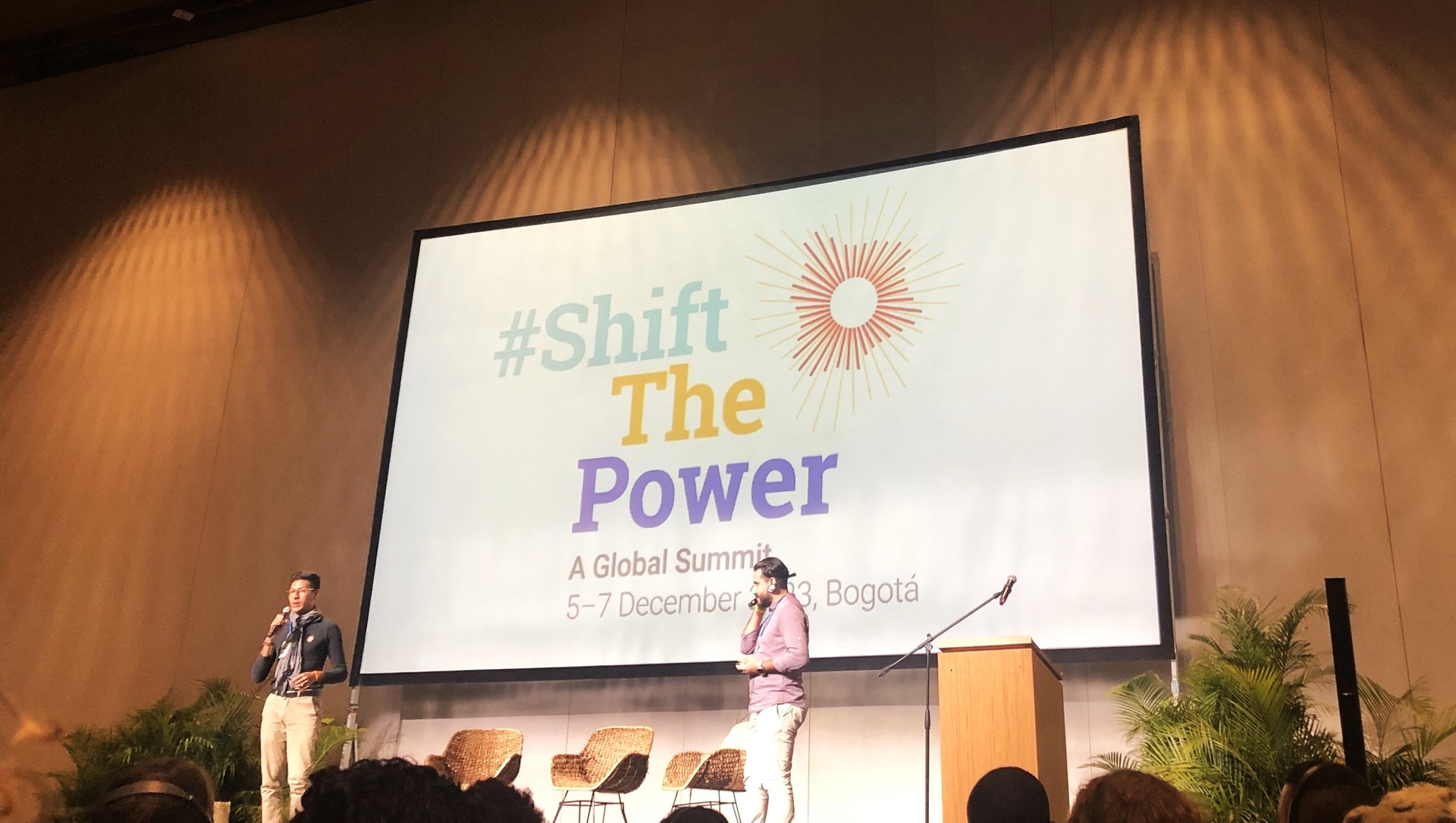

These and many more questions have to become a much stronger part of the current discussions in our sector around governance, power shift and legitimacy. I will start by talking to the women I know, some of them who are in leadership roles in the sector (or elsewhere) and the many who aren’t (yet) – so that together we can develop ideas how to achieve gender balance at the top. To the many women I don’t know: Please let me know what you think at hwolf@icscentre.org